(Ethier, 2018)

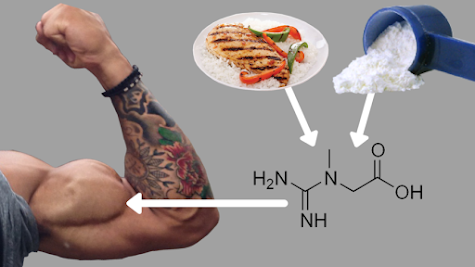

Your body makes creatine on it's own, but sometimes that isn't enough when you want to enhance your physical fitness levels. Three amino acids are added together in the liver, kidney, and pancreas to make creatine, and it enters the bloodstream where it travels to muscle tissue to be stored (Balsom et al., 1994). When we workout, our muscles use energy in the form of ATP during the first 30 seconds of exercise (Molinaro, 2020). By supplementing creatine into our diet, we are able to produce more ATP and have more energy, to build more muscle.

Most meats such as beef, fish, and poultry contain creatine (Kaviani et al., 2020), but the amounts are so small it's hard to meet the recommended levels through diet alone. Choosing the right creatine supplement is important, that's why it is recommended that users purchase creatine monohydrate. This form of creatine was tested as the purest form of creatine supplementation on the market (Moret et al., 2011).

Common side effects individuals will see when they take creatine is weight gain due to increased water retention and tight or stiff muscles due to increased strength and muscle activity (Fletcher, 2019). Another common occurrence is that the body will no longer produce creatine naturally on it's own. However, if you were to stop taking creatine supplementation, your body would begin to produce it naturally again within 2-3 weeks (Fletcher, 2019).

Remember, creatine is not a steroid, so if you want to see results, you need to continue exercising in order for the supplement to work. Otherwise, your body will simply remove the creatine as waste in your urine (Taner et l., 2011). All-in-all, creatine is recommended for individuals who want to improve their short-term, heavy exercise performance (Gillen, 2014).

References

Balsom, P.D., Soderlund, K., & Ekblom, B. (1994). Creatine in humans with special reference to creatine supplementation. Sports Medicine, 18(4), 268-280.

Ethier, J. (2018). How to take creatine for muscle growth (12 studies) [Photograph]. Built with Science. https://builtwithscience.com/how-to-use-creatine/

Fletcher, J. (2019). Energy systems ATP resynthesis and ATP-CP system. [PowerPoint Slides]. Mount Royal University Blackboard. https://library.mtroyal.ca/ld.php?content_id=35491974

Gillen, C.M. (2014). The hidden mechanics of exercise: Molecules that move us: Harvard University Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/mtroyal-ebooks/detail.action?docID=3301415

Kaviani, M., Shaw, K., & Chilibeck, P. D. (2020). Benefits of creatine supplementation for vegetarians compared to omnivorous athletes: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3041. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17093041

Molinaro, A. (2020). New insights into creatine transporter deficiency. Firenze University Press

Moret, S., Prevarin, A., & Tubaro, F. (2011). Levels of creatine, organic contaminants and heavy metals in creatine dietary supplements. Food Chemistry, 126(3), 1232-1238.

Comments

Post a Comment